Day Eleven: The Substack Writer Moonlights as a Real Journalist

And a tribute to those who are lost

Welcome all of you to day eleven of this very planned but quite unplanned adventure. There’s a certain gravity to the number eleven—it’s an adult number, and as they say in the traditional post-Seder song, eleven is the number of the stars in Yosef’s dreams. Today, eleven meant adulting in the most sobering way possible. When this war became a reality and reflection causes me to pause and take stock of what is undeniably a situation of great gravity.

It started with a gut punch in the form of the news that an Iranian missile had slammed directly into Soroka Medical Center in Beersheba, leaving 71 people with minor injuries and causing significant structural damage. When I heard about this, something crystallized for me about this conflict. You can call it tit-for-tat, you can debate military strategy, you can blame Israel all you want, but the moment hospitals become targets, you know exactly who the good guys and bad guys are.

More than 700 patients were in the hospital when the strike hit, and Iran conveniently claimed they were targeting a military command center near the hospital, but that’s a distinction without much difference when you’re targeting a facility that serves civilians of all backgrounds, including Palestinians who come specifically to be treated there.

With all this in mind, I was ’feening’ for some adventure. I started my morning with ambitious plans to reach Tel Aviv, where rockets had also fallen overnight. The trip was largely unsuccessful and I couldn’t get close to where I wanted to go, the security cordons keeping curious bloggers like me at a respectful distance from the impact sites. So I returned to Jerusalem, where the afternoon took on a more domestic character.

I found myself at my cousins’ house, challenging them to ping pong matches that revealed just how thoroughly unimpressive my athletic abilities really are. I played against two of my dearest cousins, including the bar mitzvah boy whose celebration originally brought me on this trip. The kid (well man now I guess) is genuinely impressive at ping pong—quick reflexes, strategic thinking, the kind of natural competitiveness that probably serves him well in battles against his sisters. Meanwhile, I was trying my hardest, which unfortunately isn’t saying much when it comes to paddle sports. Let’s just say that if ping pong were a metaphor for my life choices, I’d still be chasing balls that bounced off the table three serves ago.

My cousins are in the same bind as I am, desperate to leave the limbo of the unknown and get back to the good ol’ known of the U.S.A. We debated the various pros and cons of the options of transport out of here. I saw an article that flights will resume on Monday. If crossing fingers wasn’t a Christian thing, I'd be doing that as we speak. Well maybe I am doing it. You’ll never know.

I spent the afternoon spending considerable time working on my Chabad.org articles—one about yesterday’s journey to Hebron and another about the Americans and Israelis being evacuated through Cyprus as this conflict continues to escalate. I’m also in the middle of writing a personal reflection essay about my time here during the war, which should publish tomorrow I guess.

It’s strange how quickly the extraordinary becomes routine. A week ago, the idea of writing journalism from a war zone while dodging rockets seemed impossible. Tonight, it feels like just another day at the office—albeit an office where the air conditioning occasionally gets interrupted by air raid sirens and my dinner gets delivered by aggressive Israelis who sniff my accent and ask for a tip. On that note, the shawarma was better today: 7/10. The fries were trash.

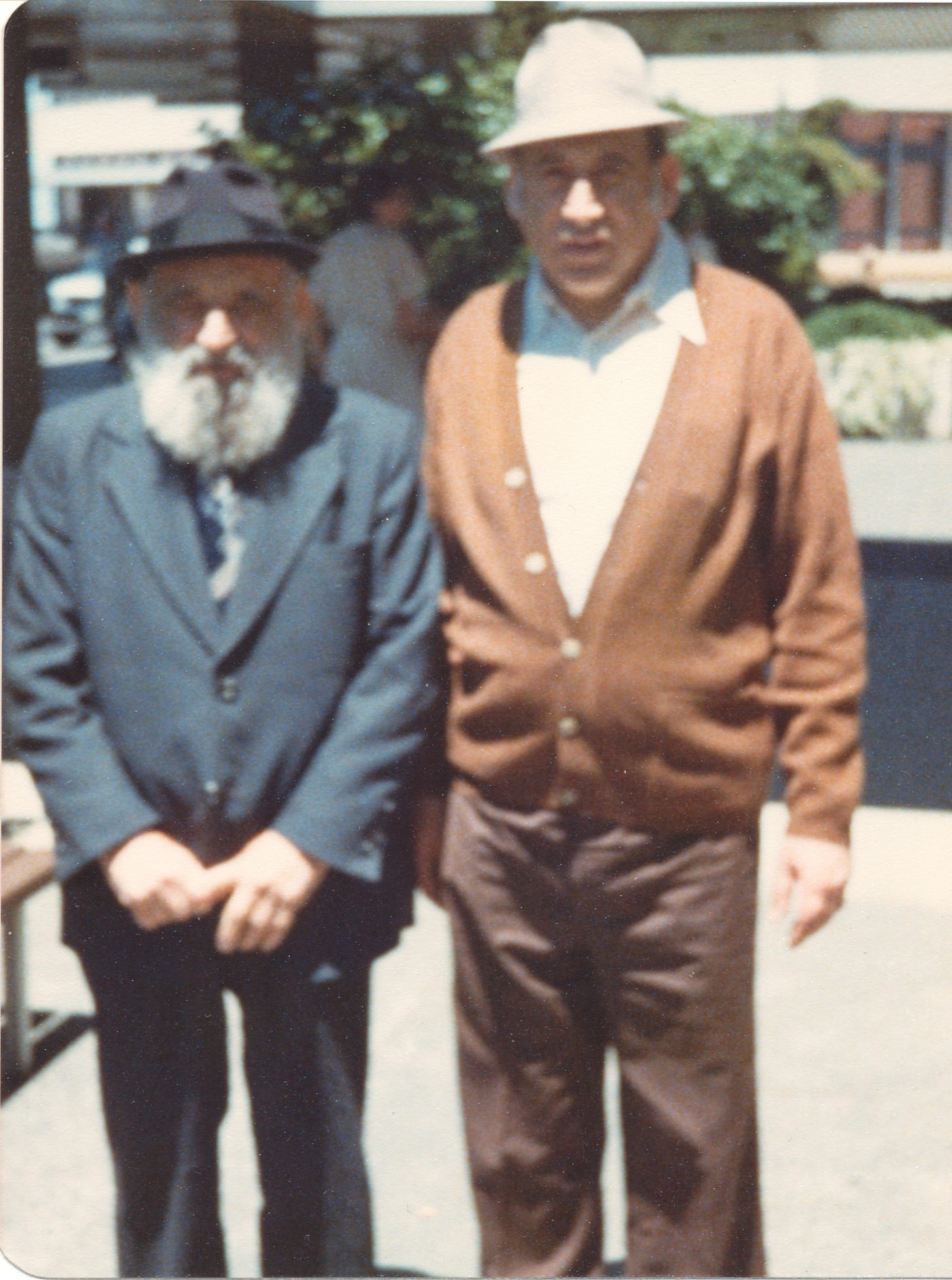

As evening approached and I sat down to write my essay about being in the Holy Land during this ‘missile crisis’ my thoughts drifted to tonight being the yahrzeit of my great-grandfather, Yisroel New (formerly Najgebirt)—Zeide Srulik to those who knew him best. I was not one who knew him. He passed away before I was born, but I have spent considerable time over the past year or so researching his story. I have become an expert on his family, channeling my uncle Moshe Rubin who did the same—and more—for my mother’s side of the family.

Notwithstanding that which I was unable to achieve, I have become quite engrossed in my family’s history and the journey of my ancestors who brought me to where I am today.

Born in Warsaw in 1894, Srulik was the third of eleven children in the Najgebirt family. Like so many Jewish families of that era, their story is one of both remarkable survival and devastating loss. In 1926, after losing their first son to medical complications, Zeide Srulik and my great-grandmother Rifktche (‘Rywcia’ in Polish—I have grown to love the Polish way of spelling things) made the journey to Australia as part of that great wave of Jewish migration seeking better opportunities and, unknowingly, safety from the catastrophe that was to come.

What they couldn’t have known was that their decision to leave Poland would quite literally determine whether their descendants would exist. Of Zeide Srulik’s eleven siblings, only he and two brothers survived the Holocaust. One joined him in Melbourne, the other lived in Moscow. His mother, Chana Feige, was murdered. Most of his cousins, aunts, uncles—an entire universe of family—were wiped out by the Nazi machine.

Tonight, as I sit in Jerusalem while rockets fall and hospitals are targeted, I can’t help but think about the parallel. Zeide Srulik fled one existential threat to Jewish survival, and here I am, his great-grandson, arriving to witness another. The geography has changed, the technology has evolved, but the fundamental reality remains the same: there are those who wish to see us erased from this earth, and there are those of us who refuse to be erased.

I am proud to be one of those who refuse. Who stands tall—and proud—to be standing here today, ready to stand again tomorrow, and the day after.

The difference, of course, between me and my rather short forefather, is that this time we have somewhere to run to that’s also worth staying and fighting for. Zeide Srulik escaped to safety, happily leaving Poland behind; I’m staying in the place that represents the refusal to need escape routes anymore.

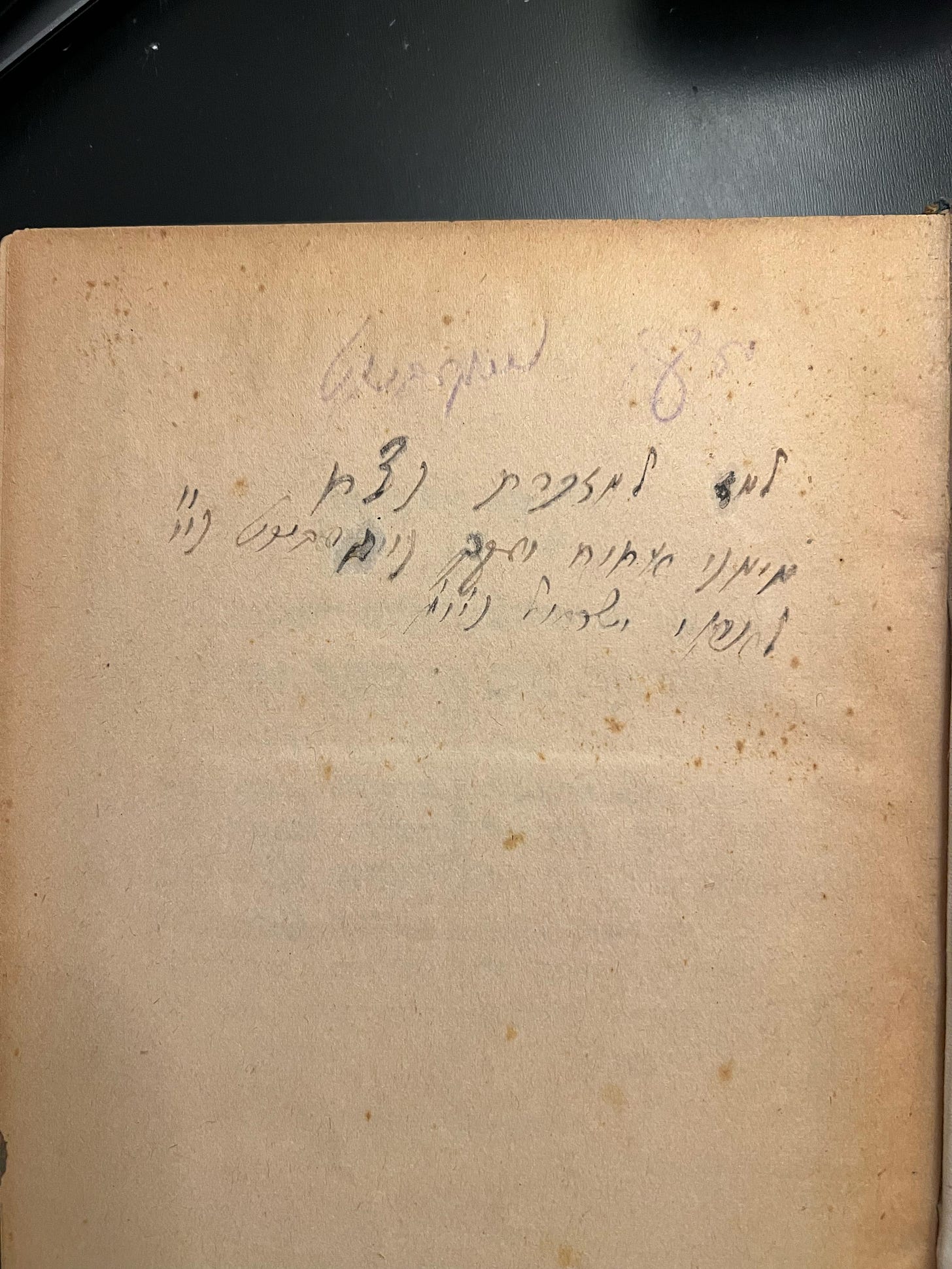

In memory of Chana Feige Najgebirt, Yaakov Najgebirt, who taught Srulik Torah when he was young and who gifted him a Tehillim that proudly bears his name, perhaps one of the last things on this earth that does. I remember his name. Yaakov died in the Warsaw ghetto two months before his mother from gangrene on his leg. Now he lives in memory as the melamed that taught Torah to the children in the Talmud Torah in Nasielsk and I will share his story and the story of his twin children, Blima and Avraham who perished in the Holocaust.

And to all the family members whose names we know and to those whose names were lost to history—tonight their great-grandson, great-nephew, distant cousin many times removed, remembers them in the city of David, in the country they never lived to see but somehow always knew would exist. They stood like Moshe Rabeinu on the precipice of Moshiach, looking over the future they had tried so hard to be a part of. They couldn’t be a part, because the One Above had other plans for them, but it is their sacrifice that allows us to enter the Holy Land and it is our responsibility to keep it safe

That’s where I leave you at the end of Day Eleven—reflecting on family history, processing current events, and marveling at how the threads of Jewish survival seem to weave through generations in the most unexpected ways.

Zeide Srulik is buried on the Mount of Olives. By Divine Providence, here I am, on its doorstep. Safety permitting, I will go there tomorrow.

Thanks for staying with me on this journey. This blog adds some sanity and routine to days that can only be described as remarkable. Tomorrow marks day twelve. According to my ill-fated plans, day twelve marks when I should have landed in Poland for the next part of my European adventure. I would’ve landed in Katowice—26 miles from Auschwitz. There’s some sort of something in that. I was supposed to be in the place of our people’s greatest catastrophe and instead I will spend the day in the location of our people’s greatest triumphs.

Until next time!

Moshe you have to stay in Israel! All your forefathers have stood for. You’re considering an ‘escape’ from the war zone!?! My friend you’ve already escaped to the promised land!